What is EBITDA?

REtipster does not provide tax, investment, or financial advice. Always seek the help of a licensed financial professional before taking action.

EBITDA Explained

It’s helpful to break down each term in EBITDA to better understand the meaning of the metric:

- Earnings – Earnings are reported on the last line of the income statement and represent net income or net profit.

- Before – The factors in EBITDA have been subtracted from revenue to arrive at net profit; the word “before” signifies that these will be added back in, meaning EBITDA will be higher than net profit or net income.

- Interest – Interest expense is related to the company’s debt structure. Some analysts believe that removing variabilities in capital expense makes it possible to more accurately compare companies with different capital structures.

- Taxes – The rationale for adding in taxes is that tax rates vary by location and therefore aren’t a measure of the business’s profitability.

- Depreciation – Again, some analysts believe that depreciation shouldn’t be included in profitability metrics because different types of businesses have vastly different depreciation expenses and they are not a measure of profitability or operational efficiency.

- Amortization – Amortization is a debt marker which, as above, some analysts believe should not be considered in measuring profitability.

EBITDA is a popular metric for heavily leveraged companies and capital-intensive industries because it reflects higher profitability than net income or operating profit.

It was first promoted in the 1980s when leveraged buyout investors needed a way to identify companies in distress that would have the cash to pay the interest on restructuring deals. EBITDA was also favored by investors during the dot-com bubble to identify companies poised for growth but laboring under heavy debt loads.

How to Calculate EBITDA

Since EBITDA isn’t typically reported in a company’s financials, investors need to know which figures to pull from the income statement and balance sheet to calculate it.

The formula for EBITDA is simple:

EBITDA = Net income + interest + depreciation + amortization

or

EBITDA = Operating profit + depreciation expense + amortization expense

Many analysts argue that EBITDA gives the most realistic view of profitability because it filters out variable expenses related to taxes, financing, and capital expenditures. Proponents compare EBITDA to the price-to-earnings ratio, although unlike the PE ratio, EBITDA is neutral to capital structure.

What is EBITDA used for?

EBITDA is a profitability measure that can be applied to businesses with different capital structures and tax profiles. Analysts say that removing interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization puts the focus solely on operations.

In addition, because amortization and depreciation are non-cash expenses, EBITDA controls for capital investments while providing insight on cash generation. This is especially useful for acquisition companies that focus on the cash potential of target businesses.

The EBITDA Margin

On its own, EBITDA doesn’t provide reliable insight into a company’s fundamentals. The EBITDA margin is actually a more useful metric.

To calculate the EBITDA margin, divide EBITDA by total revenue. Companies with higher EBITDA margins generally have more potential than those with lower margins.

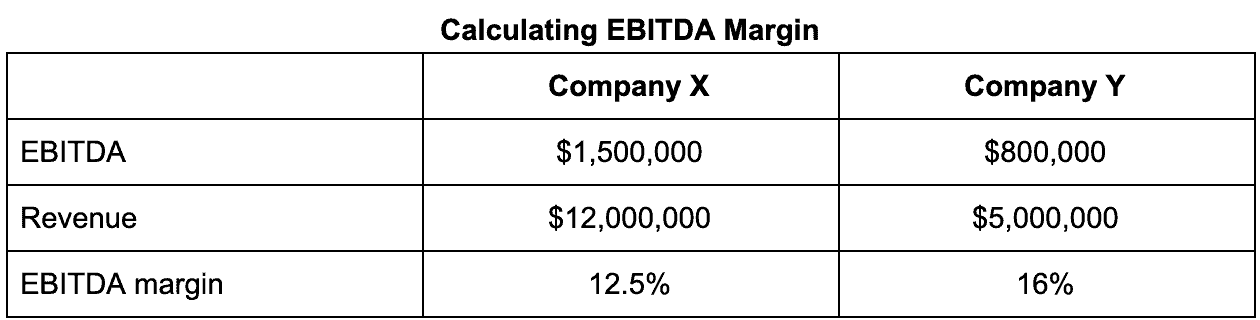

Consider the following example of two IT companies:

Company X has nearly twice the EBITDA of Company Y, and more than twice the revenue, yet Company Y would be more attractive to investors based on its EBITDA margin of 16%.

Drawbacks of Using EBITDA

Many well-respected analysts and investors—Warren Buffett among them—view EBITDA with deep suspicion. Many consider it a gimmick used to convince worried investors that the company is in better financial shape than it actually is. In fact, Buffett won’t buy companies that tout EBITDA, saying,

“Does management think the tooth fairy pays for capital expenditures?”

EBITDA can be a misleading metric because it shifts the focus away from potentially poor management decisions such as taking on high-interest debt or failing to replace aging equipment.

Hidden Hazards of EBITDA

Investors who rely on EBITDA without considering other fundamentals could get a very misleading picture of a company’s financial health. For example:

- EBITDA is a poor substitute for cash flow. While depreciation and amortization are non-cash expenses, taxes and interest are paid with cash. This means that changes in working capital investments aren’t accurately accounted for because they’re excluded from EBITDA. A company that breaks even on EBITDA will not generate enough cash to replace working capital.

- Because EBITDA is not a GAAP metric, businesses may calculate it differently and use different earnings figures as the basis for their EBITDA calculations. It is not uncommon for companies that borrow heavily or face rising capital costs to focus EBITDA over net income to distract from red flags on the financials.

- Getting back to Buffett, one of the major hazards of EBITDA is that it ignores the cost of assets. Using EBITDA as a metric of profitability assumes profits are exclusively the result of sales and operational efficiency, while the assets and capital expenditures the business needs to survive are paid for by “the tooth fairy.”

- EBITDA also clouds the issue of interest coverage. For example, ABC Widgets has operating profits of $5 million and interest charges of $5 million. The company adds back in depreciation and amortization expenses of $3 million giving it EBITDA of $8 million, which appears to be more than enough to pay its interest expenses. The problem with adding in non-cash expenses like depreciation and amortization is that the associated costs can’t be delayed forever. The depreciated equipment will eventually need to be replaced.

Ultimately, it’s up to each investor to decide how to weigh EBITDA in their overall analysis. Because it’s not a metric defined by GAAP, companies can calculate it—and report it—as they wish. Investors may be better served by using EBITDA in conjunction with more reliable metrics and fundamentals, if they choose to use it at all.